Earlier this year, Ghana demonstrated that mutually beneficial outcomes in mining disputes are possible. A dispute between the Government of Ghana and Gold Fields over the Damang gold mine was resolved through negotiation, preserving both national interest and investor confidence. That case now serves as a potential template for how other West African governments and mining stakeholders might navigate similar tensions. As global gold prices soar, surpassing $3,500 per ounce earlier this year, two of West Africa’s most mineral-rich nations are facing high-stakes disputes that are testing the balance between foreign in

vestment and indegenous control. In Mali and Ghana, governments, local firms, and international mining companies are locked in parallel confrontations that reveal the evolving politics of resource governance in a post-colonial world.

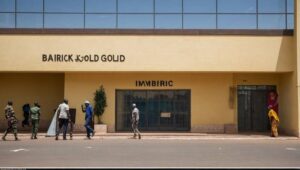

Mali: A Test of Contract, Control, and Consequence

In Mali, the showdown between the government and Barrick Gold, the world’s second-largest gold producer, has escalated into a full-blown legal crisis. On Monday, a Malian court placed Barrick’s flagship Loulo-Gounkoto gold complex under provisional state administration for six

months. The court appointed Zoumana Makadji, a former Malian health minister and accountant, to oversee the mine’s operations, though legal ownership remains with Barrick subsidiaries.

The move follows a standoff over unpaid taxes and legacy contracts, stemming from Mali’s 2023 overhaul of its mining laws. That legislation increased state royalties and demanded greater equity stakes in mining joint ventures. While peers such as B2Gold and Allied Gold have agreed to settlements, Barrick has held out, offering $370 million in tax payments while disputing the state’s claims. In retaliation, the government detained four of the company’s staff and blocked exports from the mine, which Barrick temporarily shuttered in January.

Loulo-Gounkoto is critical to Barrick’s portfolio, second only to its Nevada-based Carlin mine, and accounted for around 15% of the firm’s global output in 2024. Yet its future is uncertain. The operational permit for Loulo expired in February 2025, just after the administration period ends. Mali’s finance minister has hinted that the state may allow it to lapse, despite a renewal request filed months earlier.

While Barrick has filed an appeal and maintains that it seeks a “mutually acceptable solution,” the episode signals a deeper shift. What began as a fiscal dispute has morphed into a confrontation over resource sovereignty, legal frameworks, and the credibility of the investment climate. For Mali’s military-led government, asserting control over strategic assets is as much about political legitimacy as economic recalibration.

Ghana: Competing Claims at the Black Volta

In Ghana, the contest over resource ownership has taken a different, but no less dramatic, form. At the heart of the conflict is the Black Volta Gold Project in the Upper West Region, where Azumah Resources Ghana Ltd. and Engineers & Planners (E&P), a local mining contractor, are locked in a dispute over claims of acquisition, funding, and legitimacy.

Earlier this month, E&P publicly announced a $100 million acquisition facility with the ECOWAS Bank for Investment and Development (EBID), suggesting it had secured Azumah’s stake and was poised to develop what it called Ghana’s first wholly indigenous large-scale gold mine. A ceremonial signing was held in Accra, drawing media attention and regional political interest.

But within 24 hours, Azumah Resources issued a forceful rebuttal. The company stated unequivocally that E&P “has not made any formal offer” and “does not own any shares in Azumah.” Project Director Rob Cicchini called the event a “staged media declaration,” warning that any deal with a partner unable to fund development would be “against Ghana’s national interest.” Azumah claims E&P had previously pledged $250 million but delivered only $4 million. The company said it has since secured international backers with experience in over $10 billion worth of mining assets.

In a separate press interview, Bright Simons, Vice President of the policy think tank IMANI Africa, alleged that E&P had circulated materials using Azumah’s letterhea

d, creating the impression of a consensual transaction. “That was a very strange problem,” Simons remarked. “It misled not only the public but potentially financial institutions.”E&P, however, disputes the narrative. It claims that a legally binding agreement was signed in October 2023, structured around two $50 million payments. E&P says it has invested nearly $500,000 monthly in operations since November and that Azumah’s sudden move to raise the project valuation to $300 mil

lion, citing rising gold prices, triggered a contractual dispute. Arbitration is now underway at the International Chamber of Commerce (ICC), with both parties claiming the legal high ground. In a bid to avoid prolonged uncertainty, the Government of Ghana has issued an ultimatum to both Azumah Resources and E&P: resolve the dispute within seven days, or the state will intervene and take a decision “in the best interest of Ghana.” The move signals Accra’s intent to maintain investor confidence while ensuring that national development objectives are not held hostage by protracted private disagreement.Rule of Law or Resource Realignment?

While vastly different in detail, the confrontations in Mali and Ghana share a common thread: Who controls Africa’s gold, and on whose terms? In Mali, the state is testing the boundaries of intervention, citing fiscal sovereignty and historic injustice. In Ghana, the question revolves around capability and contractual legitimacy in a legal system that is still consolidating trust.

Importantly, both governments have avoided overt expropriation or political decree, opting instead for arbitration, judicial orders, and legal negotiation. That may reassure some investors. But others will see in these disputes a rising uncertainty about asset security, contract enforcement, and reputational risk, even in countries long seen as stable mining jurisdictions.

A Sovereign Reckoning

These disputes are not anomalies, they are a reckoning. For decades, African gold flowed outward under the authority of contracts drafted elsewhere, with terms rarely favoring local communities or governments. Now, with commodity prices soaring and fiscal space tightening, states are pushing back.

But this moment does not need to devolve into rupture. The earlier resolution between Ghana and Gold Fields over Damang illustrates that investor confidence and state sovereignty can coexist, when dialogue is prioritized and commitments are respected. Whether Barrick in Mali and Azumah–E&P in Ghana can achieve similar outcomes may hinge not only on legal positioning but also on the Government’s resolve to ensure Ghana’s mineral future is determined through clarity, competence, and public interest.

What emerges in the coming months could determine whether this moment becomes a turning point for economic justice, or simply another chapter in the long contest over who gets to mine, and who gets to benefit.